Another side of being black and indie.

Barry Jenkins’ award-winning debut film is exciting, accomplished and provocative. Ostensibly about two African-American twenty-somethings who get to know each other after a one-night stand, Medicine for Melancholy comes at race, class and gentrification from some refreshingly odd angles.

The film takes place in San Francisco. The city is, in many ways, the third character in the film and, as Micah (Wyatt Cenac) points out, there’s so much to love about it. But in a rapidly gentrifying city that has the lowest percentage of African-Americans in the country, and even fewer in the indie music scene, the stage is set for an isolating experience. Jenkins captures this sense of isolation in a number of ways. The primary way is that beyond the two main characters, the other people in the film are just props. As an audience, we don’t become engaged with them. Also, Jenkins and his cinematographer do a neat trick: The film starts out in black and white and as Micah and Jo’ (Tracey Heggins) get to know each other, color is dialed in slowly. But never fully.

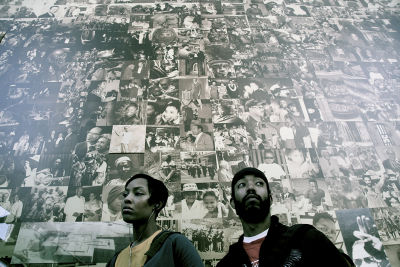

They spend the first part of their day together—after Micah tracks Jo’ down to return her wallet—in a museum of African-American history. But when Micah wants to talk about race, particularly his own sense of isolation in the indie music scene—in many ways he’s talking about SF—Jo’ begins to disengage. Race is the thing they have in common, but it also becomes the wedge between them.

Not only do we see the extent to which SF, despite its splendor and the camera’s lingering gaze on so many small and beautiful details, is isolating and lonely for Blacks (even though Oakland is right across the bridge), but we’re seeing the ways that two very different people cope. Micah’s reaction is to want to talk about isolation and frustration, his feelings of invisibility. Jo’, on the other hand, isn’t quite ready to absorb on the full implications of her blackness in a city that’s not very black. In fact, when Micah asks her what she does for a living, she says that she’s taking time to figure it all out.

And we all know that “figuring it out” isn’t such an easy thing to do, especially where race is involved. Especially after you’ve figured out how to navigate a white world. Especially after it’s been a long time since you’ve encountered another black person, let alone one who calls into question things you’ve gotten used to taking for granted. Uncomfortable, right? When Micah brings up race early in their time together, Jo says that they’re both more than the sum of their racial parts. Micah points out that society sees him as a black man, but she’s not trying to hear this. Micah is acutely aware of his blackness, particularly because he loves the indie music scene, thus his need to vent later in the film:

Everything about being indie is tied to not being black.

So it’s not just invisibility he’s dealing with, but also a sense of negation around the thing–indie music–that’s very important for him.

Which is why Oakland isn’t a viable option for him. In it’s simplest form: San Francisco represents indie—independent, but unfortunately white—and Oakland, by its omission, is posited as everything black that he’s trying to rise above. Not deny, mind you. But, like anyone, he’s looking for a place where he can follow his interests and acknowledge his own complexity. As Village Voice reviewer Ernest Hardy points out, Micah’s need is “to embody and live a more complex, dynamic blackness”. And how thrilling it must be for him to meet a black woman who’s in the scene. Finally, here’s someone who will understand!

You can see that Jo, too, is glad to connect to someone black. Once the ice breaks, there is an easy

playfulness that she and Micah show towards each other. And there are sections of the film where there’s no dialogue, underscoring that these two have a connection. But Jo is struggling to reconcile choices she’s made. You feel that her choice—accepting the largess of her white boyfriend—came at a cost, and she’s still unable to judge whether or not the cost was too high. (An aside: While we’re never told this explicitly, the assumption is that her boyfriend is white, given that she says he’s an “art curator” who’s in London. She also goes to a gallery on his behalf. My point is that the art world is notoriously devoid of people of color.) At the same time, she doesn’t want to have her situation thrown in her face, which is the effect that Micah’s questions have.

But don’t take this to mean that the movie is all heavy and ponderous. It’s a film of great beauty (the carousel scene is one in particular) and there are plenty of moments that make you smile, if not laugh out loud (“‘Superfreak’ or ‘U Can’t Touch This’? The video, not the song,” Tracey says to Micah.) Like after their clubbing when two brothas approach them at a hot dog stand and try to sell them kombucha tea. One of the guys even asks Micah if he’s properly hydrated. Only in San Francisco, right?

“Medicine for Melancholy” is a satisfying film experience, one that stays with you after it ends. After all, there’s nothing better than seeing characters who affirm their humanity and leave the confines of stereotype far behind.

Medicine for Melancholy’s NY run continues through Thursday, February 12 at the IFC Film Center.

Additional links: