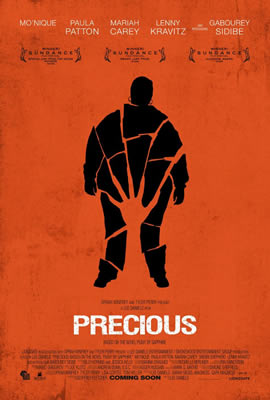

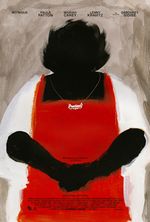

It wouldn’t be a stretch to say that, if you’re African American, you’ve probably been around or involved with at least one conversation–and maybe heated–about Lee Daniels’ film, Precious: Based on the novel Push by Sapphire. Our house has been no different. So, to all the POVs out there, I offer this from my wife, Bridgett Davis. A journalism professor, she comes to this discussion also as a filmmaker, a novelist and a blogger.

Why don’t I like the film Precious?

There are certainly a lot of reasons to like it. It’s both powerful and unforgettable. It’s beloved by critics. People I respect have championed the film. It’s marching its way to an Oscar nomination for its African-American director. It prompts debate and heated dialogue. It’s the film of the season.

So what’s my problem?

No, I’m not concerned about airing our dirty laundry, or worried that people will think all black folks are like the ones in the film. My concern is more visceral. I don’t like the film because I don’t like being manipulated — certainly not so blatantly.

This manipulation began with the novel PUSH. Its author Sapphire readily admits that Precious is a composite character. In other words, she’s a construct meant to “speak to” all the abuse that any girl in the ghetto has ever suffered. She’s a type. Rather than make her real, i.e., flawed, Sapphire made her someone who can elicit from us only two emotions on the same continuum –sympathy and pity.

Humanity is complicated. Would Oprah have loved Precious so much if she’d been more like Oprah herself, who had a baby at 14, which she says resulted from sexual abuse and its “resulting promiscuity”? Would she still have claimed to see Precious everywhere, even “waiting for the bus as I’m passing in my limo”? Or, what if Precious had been more like Sapphire, who supported herself as a young woman in New York by topless dancing and prostitution? Those who devote their lives to working with sexually abused young women will tell you that girls like Precious often are indeed promiscuous.

But then, that more complex portrayal would have messed with Sapphire and director Lee Daniels’ s agenda. Back to that in a moment.

After we’re made to feel sorry for poor Precious, we’re allowed to assuage our pity vis-a-vis a fairy-tale redemption; we walk out of the theater feeling either surprised or proud that we could “feel so much” for a girl who should be unlovable given how she looks. As someone who grew up with three obese sisters, I’m here to tell you that you can love a fat, dark-skinned girl. And she doesn’t have to be the brunt of outsized abuse to be worthy of that love. Nor does she have to be an angel. Indeed, in the film the teacher Ms. Rain’s intervention would be far more profound if Precious had been more of a challenge to deal with. It takes a lot to care about someone who’s difficult to help, who makes you work at it. And it says a lot about someone who makes that effort.

After we’re made to feel sorry for poor Precious, we’re allowed to assuage our pity vis-a-vis a fairy-tale redemption; we walk out of the theater feeling either surprised or proud that we could “feel so much” for a girl who should be unlovable given how she looks. As someone who grew up with three obese sisters, I’m here to tell you that you can love a fat, dark-skinned girl. And she doesn’t have to be the brunt of outsized abuse to be worthy of that love. Nor does she have to be an angel. Indeed, in the film the teacher Ms. Rain’s intervention would be far more profound if Precious had been more of a challenge to deal with. It takes a lot to care about someone who’s difficult to help, who makes you work at it. And it says a lot about someone who makes that effort.

As I watched the film, I kept waiting to see myself in one of the key characters. But you can’t really — unless you see yourself in the perfect Ms. Rain or the beleaguered social worker. Everyone else in the movie is a stand-in for a rash of complicated pathology: the mother is a stand in for all the dysfunction of ghetto life; the father is a stand-in for all sexual predators; Precious is a stand-in for all abused children and women. Who’s human here? Who’s genuine? And where do we as audience members get to enter? Honest cinema leaves us changed by the end credits because we have to ask ourselves tough questions: What would I have done in that situation? Are those pieces of myself I recognize up there? Have I been guilty of similar transgressions? When you can’t enter a story, when you can’t empathize with any of the flawed characters, then you don’t have to feel uncomfortable about your own culpability.

Here was a chance for many black mothers to see parts of themselves in Monique’s character. A ride on a New York City subway or a Saturday spent in Brooklyn’s downtown Target reminds us all that many black women spew angry invectives at their children — from cursing to name-calling. But those mothers can comfortably judge Precious’ mother from a distance because they don’t let their men rape their daughters in full view, don’t sexually molest their own girls, don’t throw down their newborn grandsons. They can say, “That’s not me.” And so, they — and we — get a pass.

A ride on a New York City subway or a Saturday spent in Brooklyn’s downtown Target reminds us all that many black women spew angry invectives at their children — from cursing to name-calling. But those mothers can comfortably judge Precious’ mother from a distance because they don’t let their men rape their daughters in full view, don’t sexually molest their own girls, don’t throw down their newborn grandsons. They can say, “That’s not me.” And so, they — and we — get a pass.

Ditto for black men who molest children or who participate in gang rapes or date rape. Even a man who rapes his girlfriend’s daughter can distance himself from the monstrous evil father in Precious because, hey, he doesn’t rape his own daughter from the time she’s three months old until she’s sixteen, giving her two babies.

And so the thing that film can do so well, force us to reckon with our own fallibility as human beings, gets bypassed in exchange for horror-flick shock value. Pitting an evil monster against a helpless victim is scary, but it’s not imaginative, and it’s not original, and it’s certainly not brave. Bravery is found in ambiguity, as in the film The Reader, in which a former Nazi prison guard is conveyed with such texture and richness that you have complicated feelings about her, even as you discover that she sent women prisoners to the gas chamber.

Meanwhile, caught up in our wave of emotions for Precious, we suspend our disbelief. Questions go left unanswered. What girl as old and as big as Precious endures repeated rape by her father? (Who, by the way, doesn’t even live in her home?) What makes her, by that point in her life, lie on her stomach and take it? What girl as old and as big as Precious never turns the abuse outward and becomes tough, hardened or viciously self-protective?

I’ll tell you what girl: one who is a device for a larger goal. What is this story’s larger goal? Let’s step back and look at it: Who abuses Precious? Who lets it happen? Why does she let it happen? And who saves Precious? Remember, this film is a fiction adapted from a fiction, so every choice made is done so for a reason. X was chosen over Y for a reason. Twin underlying messages run through this film like a low-grade fever. One is that black women value their worthless black men over their children. The other is that salvation and protection can be found in lesbians, who don’t rape you or abuse you or impregnate you — and offer warm, loving home environments to boot. Did Precious have to be abused so badly in order for that point to be made? Agenda cinema, anyone?

Skilled filmmakers can make you think what you’re seeing is real-life. That’s something cinema has over all other art forms, its verisimilitude. Yet the best filmmakers know how to make you feel what you’re seeing is not just “realistic”, but resonant.

This film works mighty hard to make sure I feel a certain way. And because of that, I don’t trust it. For all its gritty “authenticity”, Precious just doesn’t feel true.

Additional link:

Have you taken the Boldaslove.us black rock audience survey? It only takes 5 minutes! Click here to start.