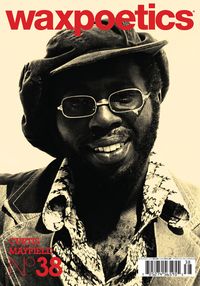

With only a few days to go before the BRC Orchestra spends two nights performing the Civil Rights songbook of Curtis Mayfield, Michael Gonzales reflects on the quiet musical giant.

While Curtis Mayfield was always been considered one of the greatest soul voices to come out of Chicago,  his guitar playing was often so understated that rock fans used to the dramatics of Jimmy Page, Prince or Carlos Santana might be weary to cite him as an influence. Yet, since the days when he was still strumming an acoustic while singing churchy sounding songs “It’s All Right” and “Amen” with the Impressions, his playing was an influence on dudes like Clapton, Beck and Steve Winwood.

his guitar playing was often so understated that rock fans used to the dramatics of Jimmy Page, Prince or Carlos Santana might be weary to cite him as an influence. Yet, since the days when he was still strumming an acoustic while singing churchy sounding songs “It’s All Right” and “Amen” with the Impressions, his playing was an influence on dudes like Clapton, Beck and Steve Winwood.

Another fan of the Impressions (and of Curtis’ guitar playing) was Jimi Hendrix. According to Jimi Hendrix: In His Own Words (Omnibus Press, 1994), the voodoo chile rocker once said, “I like the Impressions…they’re some people that need to be really, really respected. See, these are classical composers. I don’t care what their music sounds like today, because today, as things are happening at that particular time, the people that’s in that particular time don’t really know the value of it until it dies off. But now people really have to start learning the value of things as they’re living today.”

Almost makes you wish brother Jimi could’ve lived long enough to see Curtis throwing down with wah-wah, feedback, fuzz and other electro-gadgets that caused strange music to erupt from the speakers. Tracks like “Billy Jack,” Kung Fu,” “Future Shock” and “Freddy’s Dead” captured a whole new level of racial angst and musical distortion in his grooves and licks.

Danny Chavis, lead guitarist for art funk band Apollo Heights, believes that young rock star wannabes could learn from the Mayfield songbook. “A lot of guitarists try to make the instrument too complex, but they should study Mayfield’s simplicity instead of seeing how many chords they can play.”

Citing Mayfield’s 1990 “Do Be Down” as a favorite, Chavis continues. “Nothing against the influence of the Bad Brains, but some players need to forget about the fastness of the punk rock ethos and explore the roots found in playing in a gospel style. To me, Jimi Hendrix was just Curtis Mayfield with the sound turned up.”

Says rock guitarist Honeychild Coleman, “As a musician, Curtis taught me to not be afraid to experiment with different non-traditional tunings, Curtis might not have been formally trained, but that never got in the way of him branching into other sonic areas or writing and producing music for other people.”

In my humble opinion, one of Mayfield’s brightest moments as a producer and songwriter was when he began working with pioneering black rockers Baby Huey & the Babysitters. Led by a 400-pound singer Baby Huey (naming himself after an oversized duck cartoon character, his government name was Jimmy Ramey), the group had began playing at a local club called the Thumbs Up (a tiny bar on Broadway just north of Diversey) in 1965.

“They started us off at one night a week, $5 each, and all we could drink. And everyone wants to know why I got to be an alcoholic,” keyboardist and trumpeter Deacon Jones writes in his self-published book 40 Years with Blues Legends.

Hired strictly as a cover band in the beginning, Jones recalled that Baby Huey, “…was kind of lazy when it came to learning new songs. I told him he had to know more songs if he was going to make it with any band. We learned, ‘Go, Gorilla, Go’, by the Ideals, and some Four Tops, James Brown, Stevie Wonder songs. The number one song we learned that always got the crowd going was Stevie Wonder’s ‘Uptight, Everything is Alright.’”

In addition to booze, Baby Huey was also dealing with heroin addiction. In Jones’ book, he describes how one morning he was pouring cereal in a bowl at Baby Huey’s place when the singer’s “drug kit” fell out of the Wheaties box.

As the group grew in stature and began drawing in large crowds, Baby Huey & the Babysitters became less about Motown covers and more about experimentation. Writer Bob Mehr explains: “As the hippie era flowered and styles changed, the Babysitters changed along with them. Gone were the satin baseball jackets and matching suits of the band's early years; Huey began wearing African robes and grew out his Afro.

“The music took on a psychedelic hue,” Mehr continued, “and onstage Huey peppered the songs' long instrumental breaks with lascivious raps ‘I'm Big Baby Huey, and I'm 400 pounds of soul. I'm like fried chicken, girls, I'm finger-lickin' good!’ With these impromptu freestyle verses, Huey was developing what many see as an embryonic form of hip-hop.”

According to the Baby Huey’s former manager Marv Heiman, it was future superstar Donny Hathaway who first came by Thumbs Up to check out the group. "Donny came in and flipped over Huey. He brought Curtis the next night,” Heiman told the Chicago Reader in 2004. “Curtis saw him and said, 'I wanna sign him. I wanna record him.'"

Unfortunately, a few months before their Mayfield produced debut The Baby Huey Story: The Living Legend was released in 1971, Huey had died from a drug overdose while staying at the Robert’s Motel on Chicago’s South Side. In retrospect, perhaps it was Baby Huey that Mayfield was thinking about when he later composed “Freddie’s Dead.”

Though the Baby Huey album wasn’t successful at the time of release, funky stand-out tracks “Hard Times,” “Mighty Mighty,” “One Dragon, Two Dragon” and “Listen to Me” would later be sampled by Biz Markie, A Tribe Called Quest, Black Moon, People Under the Stairs, Ghostface Killah, Diamond D., Big Daddy Kane and others.

Cultural critic Nelson George has said that Mayfield “owes a debt to Norman Whitfield production on ‘Cloud Nine’ (1968) for opening up Black music and preparing Black audiences for more progressive directions.” Yet, I also believe that Curtis had simply been paying close attention to his rowdy protégés (though from listening to the album, I would guess they influenced each other equally) as well as to Sly & the Family Stone, Miles Davis and his musically radical Chicagoan neighbor Sun Ra.

After a tragic accident in 1990 paralyzed him for life, causing him to never play guitar again, Mayfield still managed be a forward musical thinker when he hired alternative soul diva Joi and funky hip-hop rocker Sleepy Brown to contribute their talents to his last album New World Order (1997) on Warner Brothers Records.

Although he sang the entire record one line at a time while propped-up in a hospital bed that had been  rolled into Curtom Studios in his new hometown of Atlanta, he never sounds fragile. “I had been a fan of Curtis’ since I was kid,” says Sleepy Brown, who co-produced the poignant track “Ms. Martha” with his Organized Noize crew. In fact, a few years before when the Atlanta based production team produced OutKast’s debut Southernplayalist – cadillacmuzik, the album was recorded at Curtom.

rolled into Curtom Studios in his new hometown of Atlanta, he never sounds fragile. “I had been a fan of Curtis’ since I was kid,” says Sleepy Brown, who co-produced the poignant track “Ms. Martha” with his Organized Noize crew. In fact, a few years before when the Atlanta based production team produced OutKast’s debut Southernplayalist – cadillacmuzik, the album was recorded at Curtom.

“Curtis worked so long and hard on that project. His bed was set-up in the basement of the studio. Sometimes he was in obvious pain, but he just worked through it. He was always asking us to criticize the work, so we could make it better.”

Joi Gilliam, who has worked with the Organized Noize crew on countless projects including her solo masterwork Amoeba Cleansing Syndrome (which has never been officially released), sang background on “Ms. Martha.” From her home in Atlanta, Joi says, “In a good sense, Curtis was real picky when it came to the material he would use. I was honored and excited to be asked to sing on the album, because Curtis had to give the thumbs up on every voice heard on that record. I knew a few singers who auctioned who had worked with other famous artists, but Curtis still turned them down.”

Although Curtis’ didn’t take home any trophies, New World Order was nominated for three Grammy Awards. Two years later, after being inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame as a soloist, Curtis Mayfield died on December 26, 1999. He was fifty seven-years-old.

Writer Michael A. Gonzales has written for Vibe, Essence and Stop Smiling. His cover story “Gangster Boogie,” on Curtis Mayfield and the making of the Super Fly soundtrack, appears in Wax Poetics #38. His Blackadelic Pop blog essay “White Boy Music” will be reprinted in Best African-American Essays 2010 edited by Gerald Early and Randall Kennedy (Random House). He currently lives in Brooklyn and writes essays for SoulSummer.com.