@felamusical

It’s hard to believe that I first saw Fela! in December of 2009. Since, then the show has gone on to win three Tony Awards the following year. And they were well deserved, as can be seen in this short, month-long revival of the play that began on July 9 and runs only thru August 4. The show remains a thrilling, immersive theater experience. Its politics come across overtly in the story of Fela’s activism through music, but also covertly in the joy of watching the triumphant celebration of black beauty on display and black bodies in motion.

The musical takes place on the night of the last performance at the Fela’s Shrine, several months after the death of his mother Funmilayo who, we learn, was brutally killed in a raid on venue by the military regime in 1978.

Storywise, this night is significant because Fela has decided to leave Lagos. His mother has been murdered, the members of his compound brutalized (we learn how in a particularly powerful scene), and despite his desire to resist, he feels he and his family are no longer safe in Lagos. However, in Yoruba tradition, before undertaking a long journey, one has to ask the ancestors for both blessing and permission to do so. Early on in the show, we see that Fela is aware that his mother is trying to tell him something.

Fela! is not a passive theater experience. Not only does the ensemble physically break the “fourth wall”—running, dancing, cavorting up and down the aisles—but the show does an excellent job of approximating how it might have felt to have actually been in the audience in Fela’s compound in Lagos via call-and-response songs, sing-a-longs, and dance lessons (have you cleaned your clock lately?). Too bad you can’t stand up for the whole show.

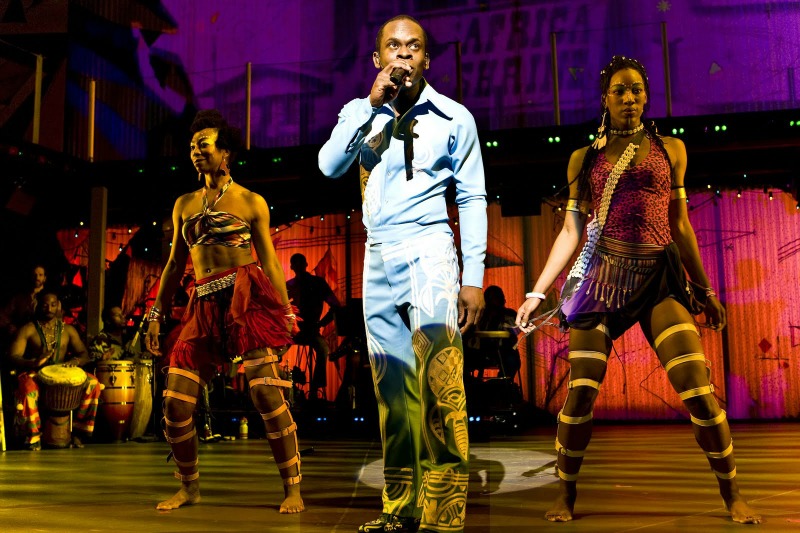

My first experience was with Kevin Mambo in the title role (who I’d seen in Lynn Nottage’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Ruined), but this time got to see Sahr Ngaujah, in the role for which he received a Tony nomination. Both of these men are great actors, and more than rise to the physicality required by the role. I remember Kevin brought a hard edge to the role. My perception here may have been influenced by just having seen as the Commander in Ruined. Sahr brings a different kind of passion and intensity to the role, which he completely inhabits. You can see the difference in his performances from 2010 to now in a clip from the Tony Awards performance. At this point, he’s settled into the role even more, deeply embodying Fela Anikulapo Kuti. He even stayed in character when he broke from the story to playfully deal with a an audience member, who wanted him to share the massive joint he was puffing on.

Photo credit: Sara Krulwich for The New York Times

Much of the original cast has returned. From Antibalas handling the music; to the Queens, to Rasaan-Elijah “Taju” Green on djembe; to Sahr himself. There’s great continuity among this group, which enables them to go from 0-60 in no time. And you get to sit through two-plus hours of Bill T. Jones’s great choreography.

Memory is hazy, but some things about this version seemed different. For example, “B.I.D. (Breaking It Down)” is a necessary party of the story. Here Fela explains how he created Afrobeat by combining various musical elements—highlife, afro-cuban music, the heavy bass line and James Brown’s funk—into something greater than the sum of the parts. But this explanation felt more impactful the first time I saw it.

This version also seemed to expand the role of Sandra Isadore, the black American who, upon meeting Fela in 1969, introduced him to the ideology of black power. On one hand it was a nice to see a new dance routine that involved books from across the spectrum of black liberation ideology. After all, where else do you see dancers moving around with books by Malcom X, Stokely Carmichael, Angela Davis and others? That said—and while I acknowledge her considerable vocal ability–she ultimately annoyed the shit out of me.

Beyond that, I’m not sure what the musical gained by giving Sandra Isadore, here played by Paulette Ivory, such increased spotlight. I’m not sure the musical needed to give Sahr/Fela a female vocal counterpoint. She has an absolutely fine voice. But there was something about it that took me out of the world of the Shrine, some kind of incongruity that was more distracting than additive.

Photo credit: Chad Batka for The New York Times

Also, there’s no discussion of Fela and AIDS. That’s partly, I think, by design and the fact that the producers have framed the story around this last night at the Shrine. There’s no way that this could be a strict autobiography (it already runs 2 hours and 40 minutes). I bring this up not as a mark against the musical, but just to manage expectations. Fela and AIDS is an entirely other story. What you’ve got here is a focus on his resistance to a corrupt state and his fight for justice.

All that said, the crossover scene—where Fela makes the journey to the land of the dead to consult with his mother—is still powerful and visually thrilling. The show’s great use of black light, screens, costumers and choreography expertly evokes Fela’s otherwordly journey. And, like Lillias White before her, Melanie Marshall conveys the regal, groundbreaking figure that Funmilayo must have been to her son and to so many Nigerians.

And a special shout-out is in order for Ismael Kouyate, who hails from a family of renowned artists and praise singers from Guinea, West Africa. He is part of the ensemble, but his voice is incredible in the way it pierced strong and clear through all the other sounds of the musical. If you want to check him out, he lives in NYC and performs with his band Ismael Kouyate: Waraba Band.

The final scene with the coffins remains a sad but stinging critique of our society that seems replete with so much injustice and murder. The names on the coffins—Oscar Grant, Troy Davis, Ken Saro-Wiwa, Rodney King, James Campbell, Sean Bell, Trayvon Martin, Citizens United—are powerful reminders that justice still has to be fought for. It’s even more sad to realize that there will always be names to add. However, what it does is bridge this look at Fela’s life (he died in 1997) with the fight for justice today. In that way, the musical is very much in the audience’s face about need for justice that is still present.

Should you run to get tickets for this show? Absolutely! Sitting there, you are reminded of how rich an experience Broadway can be.

Additional links: