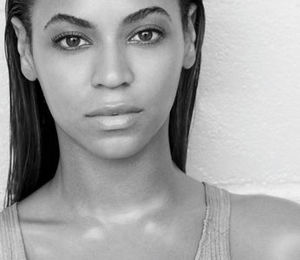

Beyonce Knowles, who plays Etta James in the upcoming movie "Cadillac Records", was profiled in Sunday’s New York Times. Here are some thought-provoking excerpts:

As she learned the history of Chess Records — which added amplification and urban sophistication to the Delta blues on recordings by giants like Waters and Howlin’ Wolf, and helped to usher in the rock ’n’ roll era with artists including Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley — Ms. Knowles said she felt an extra obligation to the project as a musician.

“I realized what an important story it was, especially for my generation,” she said. “We don’t know where rock ’n’ roll came from, we don’t know that the Beatles and the Rolling Stones got their inspiration from people like Muddy Waters and Little Walter.”

Jump to:

When she returned to finishing the album, Ms. Knowles said she was being drawn to songs and sounds that had previously been off-limits for her. “The music I made before and after the movie were very different,” she said. “I was a lot more bold and fearless after I played Etta James, because of course some of the character stays with you. Some of the music I would have been afraid to make, I wasn’t. I got more guts, more confidence as a human being."

And finally:

Above all Ms. Knowles hopes that she will be able to look back on this moment as a turning point, both personal and professional. “When you’re a pop star, it’s a little conservative, you always have to stay in a box,” she said. “You have fans that are 5 and fans that are 65, there are so many people that want so many things. But Etta James was the queen of rock ’n’ roll, soul, R&B, jazz — she did it all, and she always made it her own. After playing her and singing her songs, I thought, it’s time for me to challenge myself and do whatever I’m inspired to do."

First, I say bravo for Ms. Knowles. I actually want to see "Cadillac Records" and her portrayal of Etta James and, more importantly, I’m intrigued enough to hear her album, particularly since she’s bucked the trend of pop artists having a ton of guests on their albums. In fact, she has none: It’s all her.

On the other hand, I take this piece as instructive on the extent to which Black life remains largely circumscribed. Here’s a young woman who’s known the world over–according to the article between her solo efforts and those with Destiny’s Child, she’s sold 75 million albums–but she’s just now giving herself permission to explore "songs and sounds that had previously been off-limits to her." Who put them off-limits? Her management? Her label? Her family? Her community? And to what extent did she self-censor? The latter is almost always a factor of what influences you have around you

If she’d never done this movie, we’d probably be getting another rehash of stuff she’d done before. (Side note: At this point, I have no idea what this new album sounds like, or whether or not it’s more of the same or anything new. All I have is some hope.) But I’m feel confident to say that she’d certainly have no connection to where she stands on the continuum of Black music, and I’m doubtful that she’d be open to the greater possibilities for her music at this point in her career. Okay, maybe she would, but there’s nothing to suggest that 1) she knew what questions to ask or 2) that anyone around her–management, label, family, husband Jay-Z–was thinking about anything beyond the next Top 10 hit. To paraphrase Jay: Nobody was trying to be intervenin’ with the sound of her money machinin’.

But this is the promise of the new Black imagination. Where her curiosity can find itself connected and fed by a larger community of people who have been engaged in the kind of creativity she’s just now discovering. That will prevent her from leaving one vacuum, just to enter another.

That also means that, as a community, we’ve got to applaud Beyonce for taking a step in this direction. Not without constructive criticism where it’s warranted, mind you. And remember, the other promise of this new age we’ve entered, is that maybe, just maybe, artists of color will take chances to develop and explore in the same way that, say, Woody Allen or David Byrne have been done.

That would be true artistic equality.

Additional links: