@tanehisi

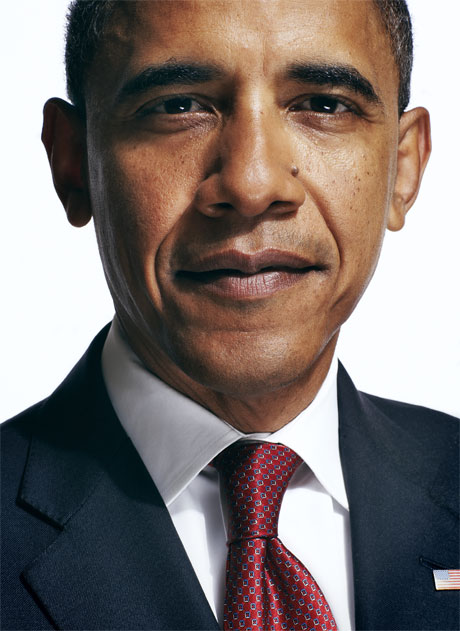

photo credit: Nigel Parry/CPI

When I say you have to read The Atlantic‘s Ta-Nehisi Coates’s exposition on Obama, race and the failure of integration, don’t roll your eyes at its length, as you’d be doing yourself a huge disservice. This is really a tour de force and crystallizes what so many of us have felt: That this political and cultural opposition that’s been mounted against Obama is about more than policy disagreements. The pink elephant in the room is race. Here Coates talks with the magazine’s editor Scott Stossel about the piece:

There’s a lot to think about, so I’m going to excerpt a few passages. Emphasis is mine.

The irony of Barack Obama is this: he has become the most successful black politician in American history by avoiding the radioactive racial issues of yesteryear, by being “clean” (as Joe Biden once labeled him)—and yet his indelible blackness irradiates everything he touches. This irony is rooted in the greater ironies of the country he leads. For most of American history, our political system was premised on two conflicting facts—one, an oft-stated love of democracy; the other, an undemocratic white supremacy inscribed at every level of government. In warring against that paradox, African Americans have historically been restricted to the realm of protest and agitation. But when President Barack Obama pledged to “get to the bottom of exactly what happened,” he was not protesting or agitating. He was not appealing to federal power—he was employing it. The power was black—and, in certain quarters, was received as such.

And on the impact of racism:

Racism is not merely a simplistic hatred. It is, more often, broad sympathy toward some and broader skepticism toward others. Black America ever lives under that skeptical eye. Hence the old admonishments to be “twice as good.” Hence the need for a special “talk” administered to black boys about how to be extra careful when relating to the police. . .But when President Obama addressed the tragedy of Trayvon Martin, he demonstrated integration’s great limitation—that acceptance depends not just on being twice as good but on being half as black. And even then, full acceptance is still withheld. The larger effects of this withholding constrict Obama’s presidential potential in areas affected tangentially—or seemingly not at all—by race. Meanwhile, across the country, the community in which Obama is rooted sees this fraudulent equality, and quietly seethes.

On Obama’s impact on the black imagination:

Whatever Obama’s other triumphs, arguably his greatest has been an expansion of the black imagination to encompass this: the idea that a man can be culturally black and many other things also—biracial, Ivy League, intellectual, cosmopolitan, temperamentally conservative, presidential.

A black man in the Oval Office cuts to the core assumptions about whiteness and privilege. After all, Obama, like many of us, is prohibited against retaliating, especially in anger, against those forces that have tormented him since the day he took office. Coates goes onto say this:

The idea that blacks should hold no place of consequence in the American political future has affected every sector of American society, transforming whiteness itself into a monopoly on American possibilities. White people like [late US Senator Robert] Byrd and [National Review founder William F.] Buckley were raised in a time when, by law, they were assured of never having to compete with black people for the best of anything. Blacks used inferior public pools and inferior washrooms, attended inferior schools. The nicest restaurants turned them away. In large swaths of the country, blacks paid taxes but could neither attend the best universities nor exercise the right to vote. The best jobs, the richest neighborhoods, were giant set-asides for whites—universal affirmative action, with no pretense of restitution.

As well, he later offers this sobering thought:

An equality that requires blacks to be twice as good is not equality—it’s a double standard. That double standard haunts and constrains the Obama presidency, warning him away from candor about America’s sordid birthmark.

And this:

Thus the myth of “twice as good” that makes Barack Obama possible also smothers him. It holds that African Americans—enslaved, tortured, raped, discriminated against, and subjected to the most lethal homegrown terrorist movement in American history—feel no anger toward their tormentors.

One of the many things Coates does masterfully in his writing is provide such rich context to the larger points he makes. Which provides ways, I think, for readers of many perspectives to engage with his work.