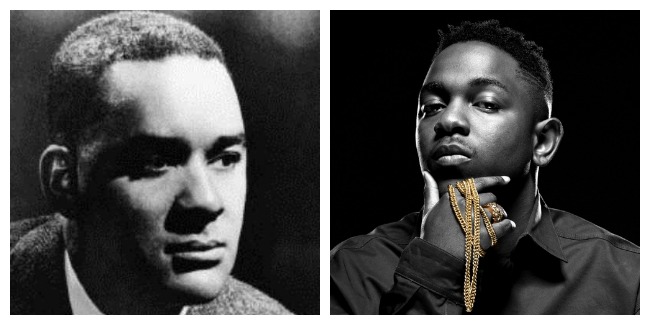

In her recent piece for the Los Angeles Review of Books, “When The Lights Go Down: Kendrick Lamar and the Decline of the Black Blues Narrative”, Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah brilliantly argues that Lamar is a direct descendant of Richard Wright, that he is in fact a rare young writer “quietly committed — like Morrison — to telling stores about the community most familiar to him.”

She writes:

“What makes him important is the way in which the autobiographical good kid m.A.A.d city is so novelistic and so eloquently anchored in the literary blues tradition of which Ellison wrote. Lamar is equal parts oral historian and authorial presence, and more than many authors writing today, he has captured all of the pathos and grief of gun violence, poverty, and the families who carve their lives out amidst all of that chaos.

Lamar has offered up his hymnal for a lost generation, a defense for the black family, and in his jumpy prosody, his shell-shocked sensitivities, his clipped memories, and recorded conversations, he has produced “a novel from life” that single-handedly revives the long lost, suppressed literary tradition of young, working-class black boys on fire, with pens smote in hell, telling us how they become gifted, tenderhearted, black men — something we have been missing even though no one seems to notice it.”

And she puts forth the astute observation that a class-based schism between black writers and black readers is the real reason the marketplace teems with urban lit titles:

As some literary black authors struggled to find a culture of readers who looked like them, their would-be readers seemed to be thinking the inverse of the question: where are the literary writers who are writing stories that sound like mine? The post-racial generation had created their own disconnect, and the authors of urban fiction were vampiristic. They saw a void and filled it — cheaply, but they filled it.

They became the writers who were still speaking to black and Latino Americans who were slipping through the cracks, a group of people the new literary generation seemed reluctant to acknowledge as an audience or as subjects. And their failure to do so is what makes work that deeply and realistically deals with class (like the fiction of Z.Z. Packer, Junot Díaz, Edward P. Jones, the reporting of Jelani Cobb, the early music journalism of writers like Bonz Malone and Touré, the theoretical work of Tricia Rose and Greg Tate, and the poetry of Thomas Sayers Ellis and Nikky Finney) so necessary — and it is also why Lamar’s project is more relevant than ever.

You can read Ghansah’s full critique here.

And consider supporting the Los Angeles Review of Books, a non-profit cultural site that has — in this world of shrinking literary criticism — taken a revolutionary stand for “curated, edited, expert, smart and fun opinion written by the best writers and thinkers of our time.”

Additional links: