“Free your miiind and the rest will follow…” sang mellifluous girl group En Vogue back in the day. We have heard versions of these words from pioneering afro-futurists like P-Funk, Sun Ra, and a host of black musicians who were as respectful of tidy music-biz categories as they were of conventional notions of space and time. Kenyan American visual artist and sculptor, Wangechi Mutu’s survey of work from the mid-90s to the present, now showing at the Brooklyn Museum, hews to this tradition of unapologetic derring-do mashed with complete irreverence for any and all socially constructed boundaries. While viewing the over two dozen art installations (there are fifty pieces in all, including a collection of sketches) I overheard a man behind me ask, “Just curious? Why motorcycles?” Many of Mutu’s collages feature women with motorcycle feet. I felt like responding, “Because they’re fast?”

Amid the undeniable beauty of Mutu’s stiletto-heeled pouty vamps, there is evidence of the still festering wounds of war, colonialization and greed which continue to plague the African sub-continent

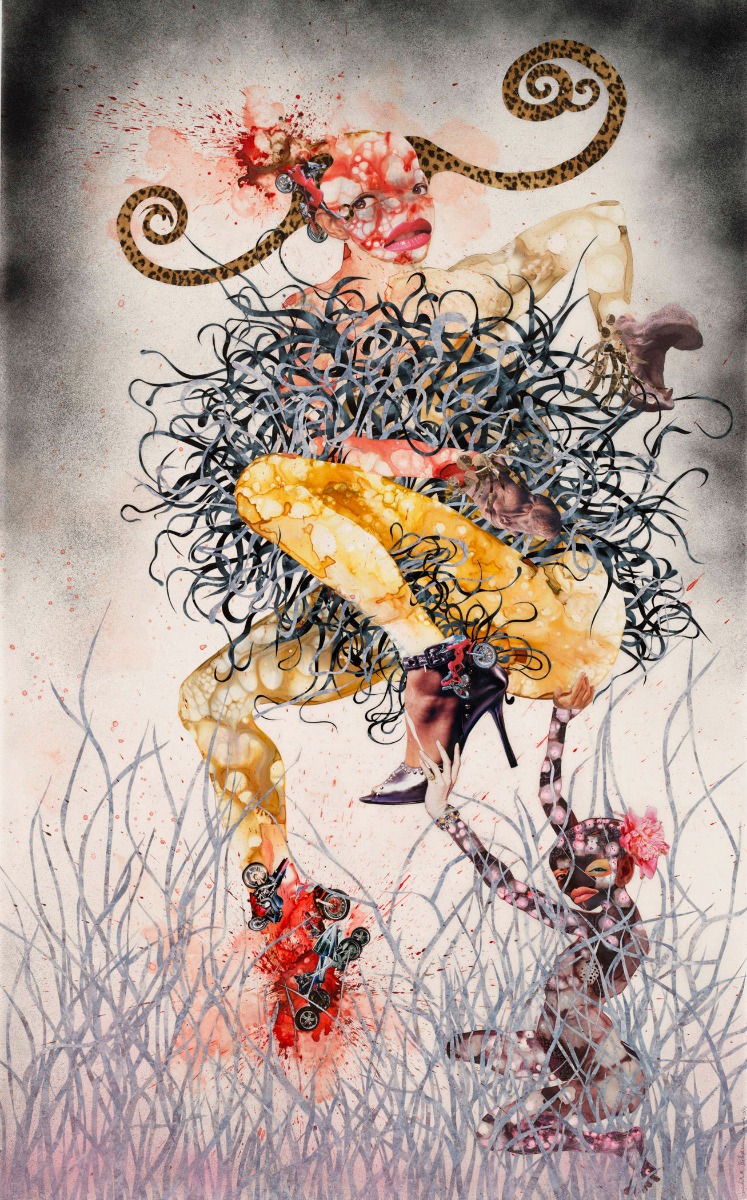

But these pieces aren’t simply commentary on female empowerment or paeans to women’s liberation. Like the frequent blood-like splatters which cover the blank spaces of her Mylar canvasses, where in at least one case the splatters are encrusted with glitter and pearls, like an exotic flower, these women aren’t simply anything. As for paeans, it’s hard to say what if anything is being celebrated or praised. Amid the undeniable beauty of Mutu’s stiletto-heeled pouty vamps, there is evidence of the still festering wounds of war, colonialization and greed which continue to plague the African sub-continent and other regions of the black diaspora. Those badass motorcycle body parts could very well be symbolic artificial replacements for real live flesh and blood African limbs compromised by bottomless Western greed: Greed for diamonds, gold, animal skins and cheap labor. These awesome women, totally hip to the scene, seem to be saying: ‘Yeah? Here are your riches, and here’s our pain.’ The viewer doesn’t get to choose. Within these collages, the beauty and the horror come at you full speed, and at the same velocity. These two ideas, typically viewed in contrast, do not merely sit side by side, contained within their own designated spheres. They are one and the same, a single packaged unit, and I love Mutu for it, because never once during the entire exhibit did she give in to any need for pretense. The pieces–surreal, unreal, intergalactic, whatever–felt very direct and honest. Portraits by an Artist as her Raw Authentic Self.

The viewer doesn’t get to choose. Within these collages, the beauty and the horror come at you full speed, and at the same velocity.

As I took in Mutu’s Fantastic Journey, I noticed a recurring theme around nature. From the first installation I viewed (“Amazing Grace”), to the last two (“The End of Eating Everything” and “Eat Cake”), I was swept up into a world of chirping birds, crashing waves, mushrooms that act like jellyfish or vice versa, earth, wind, water. These three films act like cinematic bookends: “Amazing Grace” is a short video of the artist singing in her native Gikuyu language, as she wades into a turbulent Atlantic Ocean until overcome by large waves. By the end, Mutu floats as the now calm waves gently rock her. No longer a storm, her song sounds like a lullaby. In mere minutes we go from turbulence to a hypnotic calm. Mutu’s loose white dress, arms and legs gently flail with the water. She’s now morphed, it seems, into a live version of one of her famous painted jellyfishes.

The other two videos are clearly comments on consumption, or over-consumption. “Eat Cake” features Mutu in a gothic setting. She repeatedly pushes back her wild hair, as she squats near water, under a tree, with the ominous sounds of birds in the background. Mutu digs her claw-like nails into a three-tiered chocolate cake, making quick work of it. “The End of eating Everything” is an animated video featuring recording artist, Santigold as a planet-like being in motion, covered with arms, wheels, tentacles, as well as spore emitting smoke. The video opens with the words, “hungry, alone and together.” Like “Amazing Grace,” “The End of eating Everything” has an ambiguously hopeful ending. We screw up, the worst happens, then– We start over.

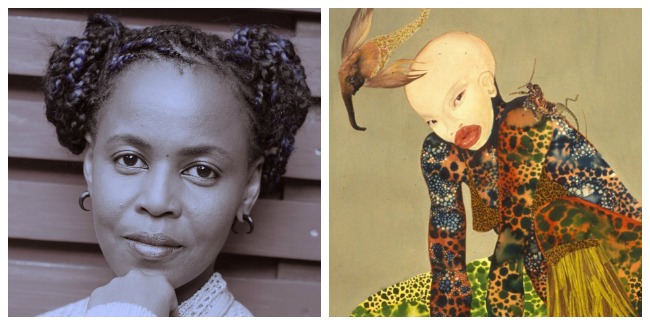

I liked “Riding Death in My Sleep,” (first image above) if for no other reason than its title, as well as “One Hundred Lavish Months of Bushwack” (below). Mutu’s bald women, with their distinctive eyes and full lips, hint at a sensuality and power I found sly and delightful. Look closely at those mushroom heads in “Riding Death.” They seem to be made of what I will call womanly flesh, all the more intriguing as the stems resemble phalluses. It was interesting as the collage was not done in any number of clichéd ways that one could imagine. There’s more violence in “Bushwack” (I remember at least one shattered foot, and a blasted skull) but it is mediated by the image of a younger woman or girl, holding up the older woman whose body has been so violated. The unharmed girl, sheltered under the body of the elder woman, has a flower behind her ear, and her skull and pelvis are covered in pretty gold stars. This lovely, be-jeweled, be-flowered girl, both delicate and brave, enables her injured elder to fight an army of tentacled creatures who are threatening to engulf and further harm her. By the looks of it, motorcycle replacement limbs and all, the elder woman, and girl, are winning.

There’s much that will leave you, yes, a little exhausted. We are a screwed up species. But there’s a great deal more that will leave you quite exhilarated.

Wangechi Mutu: A Fantastic Journey can be seen at the Brooklyn Museum through March 9, 2014.

Camille Goodison is a graduate of the Syracuse University Creative Writing Program in Fiction. She also completed her doctorate in literature at Binghamton University. Her work has appeared in Callaloo, Calyx, Relief, and Teachers and Writers Magazine among other publications.