BMD: This collection of poetry, Go Find Your Father/A Famous Blues, is essentially two-books-in-one, with two distinct titles and covers presented in a flip-over style. It reminds me of the A & B sides of an album; it also brings to mind the “flip side” of a point-of-view — two ways to see one person, or subject or situation. What was your thought process in choosing such a design?

HH: I had been meditating for a while on literal manifestations of subconscious drives that sort of bend our wills in two directions at once: toward what we think we desire or wish we could desire on the one hand, and on the other toward the resolution and re-integration of data stored in our cells disguised as anything from forgetting to superstition, information we carry around with us about anything from past traumas to past lives, and devote our egos and other addictions to suppressing. I think in the end that fragmented state we all tend to cling to to protect our fragile or gullible egos from time to time, undermines our evolution, and I wanted to force some of the subconscious drives in me to the surface, both very literally in the form of the letters throughout Go Find Your Father and more mythically in the form of the blues poems throughout A Famous Blues. I also wanted to develop a dynamic between lived experience and its tributaries, the way Blues music does, the songs sob in such a deadpan way that they transmute sob story mentality and become joyous and healing experiences in listening, soothing without being untrue, I wanted to accomplish that in several different textures and it just felt right to divide it into two symbiotic acts, one devoted to the personal history and one to the mythic imagination it helped produce.

…poetics, or what makes something poetry, is not as much about where a line breaks or stays, as about where rhythm and a kind of tone science coalesce to create a unique universe I long to enter and know for the duration of the poem

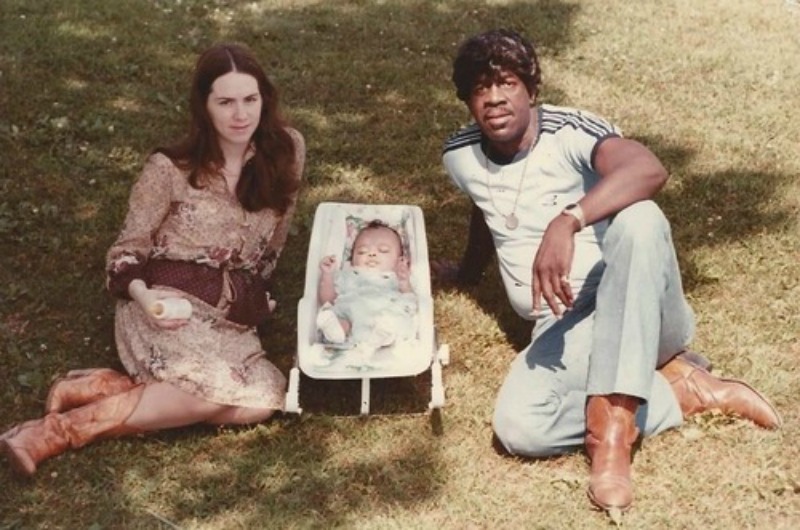

The collection is rich in archival documents that reveal key aspects your father –hand-written notes, his newspaper obit, business letters, his royalty statements (used wallpaper-style throughout), family photographs. You are an archivist as well as a poet. What resonance do these documents bring to the text? Why was it important for you to include them?

Some of the text chronicles my father’s tendency to turn love into an act of violence, and in the rough undertow of those vivid and haunting descriptions, it’s difficult to make the disclaimer ‘but it was ok, forgive that, he was a great beautiful spirit in other ways, such is the karma of a universe like ours, etc.’ I see the writing and the archival material as a sort of jazz ensemble, they improvise with one another and the tone generated contains all of the manifold layers of a complex truth, some that would be dismissed without the coalescence of what I’ve written with the documents that inform it as physical form, the documents jut out of the writing like festival balloons or rigid fences or regal but unkempt monuments, they force the writing into a context and a form it often wants to resist or repudiate.

Some of the text chronicles my father’s tendency to turn love into an act of violence, and in the rough undertow of those vivid and haunting descriptions, it’s difficult to make the disclaimer ‘but it was ok, forgive that, he was a great beautiful spirit in other ways, such is the karma of a universe like ours, etc.’ I see the writing and the archival material as a sort of jazz ensemble, they improvise with one another and the tone generated contains all of the manifold layers of a complex truth, some that would be dismissed without the coalescence of what I’ve written with the documents that inform it as physical form, the documents jut out of the writing like festival balloons or rigid fences or regal but unkempt monuments, they force the writing into a context and a form it often wants to resist or repudiate.

In addition I think it’s important for us to share things like contracts and legal statements when it comes to black artists, to create a commons wherein we can educate ourselves about how we are treated by the entertainment industry, to hold ourselves and our employers accountable for not turning artists into new slaves by casually exploiting our creative power and our biological need to express, in order to fund the interests of record executives or create trends that are then appropriated or turned into fodder for backlash the way some radio rap is treated. Our history as we know it as black artists is so often censored, suppressed, and completely distorted, that we have to militantly mark our lives with their true insignia, is how I feel, if we don’t become our own living arkive the western world will gladly wipe our memory bare with its selective and seductive and damaging fictions, so this book allows me explore my real memory in relation to the hard facts that archival documents about my history present. As I uncover more of this archival material more new work is born so it has also become a generative tool.

Go Find Your Father is an intimate, autobiographical collection, sometimes painfully so. How difficult was it for you to reveal difficult parts of your personal life? Are there writers or poets who are influences when it comes to revelatory memoir?

As difficult as it was in places to really come to terms with the honesty I was being inspired to deploy like a kind of healing salve for myself and hopefully for readers as well, as much as I had to struggle with my own fear of intimacy to access it, it was still easier than harboring those feelings in their unexpressed or unarticulated subtle forms, before articulation they are blockages, after it they’re these devastating freedoms from tired excuses, you’ve reached the rotting root and yanked it forth so there’s space for something new and clean to grow, one hopes it’s not new trauma to replace the comfort or familiarity of the old, one knows all that’s left is love and that’s the hardest moment ever to come to terms with in a way, to come to terms with having come to terms. It saves us. I’m constantly inspired by people like Amiri Baraka, Claudia Rankine, Charles Mingus, Anne Carson, and Jimi Hendrix, whose letters to his own father directly inspired the form of this text— among many others who seem to take a similar approach to self-revelation as a form of self-actualization, without flinching or apologizing, in the spirit of moving on.

GFYF is also an epistolary series of poems, each opening with Dear Dad. These letters have the accumulated effect of progressing toward a deeper connection to and forgiveness of your father. What surprised you the most in writing these poems/letters?

I was shocked at how safe the address made me feel, like I could admit anything to this idea of my dad the letters at once create and dispel. I could be as natural as I needed to be, I could commune with my favorite person again without being afraid he would disappear again, I was shocked by how much of his spirit I was able to carve out of my own improvised confessions.

These two collections document your father’s own story even as they explore your relationship to him. PORTRAIT OF MY FATHER AS A YOUNG MAN reads like his own words transcribed verbatim, while elsewhere you share the battle to retain the publishing rights to his songs. Given how many stories of African-American life have been lost to history, was your motive to document Jimmy Holiday’s story, to ensure its place in the record, so to speak?

Absolutely. His story being on the record clears space and energy for a multitude of stories like his that go untold or even undiscovered by their direct inheritants. I often echo jazz genius Sun Ra’s beautiful dare “show me your myths—” sometimes in order to do that we have to first show our men and women as they are, the heroic and the anti-heroic, the triumphs and the despairs, what I sometimes call the ecstatic mundane. I also needed to account for my own understanding of the context I’ve been born into, in a literal way, to map my identity in territory that is karmic and beyond the egoic self, to access the trove of biases in my subconscious that might guide my will to distraction unless named, called out, released, and re-imagined. I think when a parent is absent for any reason during one’s childhood, that relationship occupies the bulk of one’s subconscious life, all the gods and monsters mimic it in attempt to reconfigure bliss from sorrow, presence from absence, love from love, and so I wanted to take a closer look at the feelings I harbor about that void and unvoid, and how I project them onto current interactions and passions, etc.

At the same time, in the acknowledgements for A Famous Blues, you say, “Let us move forward toward our myths.” What role does a contemporary poet like you play in modern-day mythmaking?

I think poetics, or what makes something poetry, for me, is not as much about where a line breaks or stays, as about where rhythm and a kind of tone science coalesce to create a unique universe I long to enter and know for the duration ofthe poem, and one I won’t forget beyond the work’s valence. I want to be electrified by a paradigm only the mind of that particular work’s ecosystem can assemble and bring forth into what feels like eternal existence. A great poem is a great myth. It has its heroes and its calls to duty even if they are abstract, it tells us how to be for it, how to treat it and how to treat ourselves within it, toward the highest degree of naturalness, the way a good myth tells us how to be for the world at large, is that presumptuous and that brave. And beyond the mechanics, I am devoted to sharpening the contours of the myths that enhance and liberate diasporic consciousness for all members of the African Diaspora. That means turning tropes like militancy and ghetto fabulousness and the jazz idiom, our way of improvising enlightenment, into shelters for our deeper common themes, the way we casually do by deifying our entertainers and leaders and fathers, no matter what they are or do. I want to be able to view these systems from self-determined angles, which means, research the grit of figures like Miles Davis and Monk and Billie Holiday and MLK, and my own father, assuming that what we think we know of these people who are at once so familiar and so far away, is misguided and often intentionally. I want to inspire the taking of our thoughts back into our own hands, from the raw archival material of them, to the myths that they free us to make. I think because poetry is free to shape-shift, it’s the right place to do this kind of work, to herald the black myth as a living and evolving myth.

Music and musicians figure prominently in your work, as if music is the literary standard off of which your ideas riff. Is that inherited from your father? Is music how you best connect to him, as his legacy?

Music is the healing agent that saved my father from his lot as a sharecropper when he was just an adolescent, so without riffing off of it his legacy would be gibberish to me. On top of that, I see music as a sort of food group with a clear nutritional value and I’m serious about what music I consume and repel, sound frequencies affect our DNA toward healing or the opposite. Music is also the place where stories like the one I tell throughout this work, are often told very explicitly. When my father sings about Hollywood he’s being literal about what he was doing at the time. In digging through the archives of his music, I am able to learn more about him as a man, and register the myths that allowed him to become himself. I’m moved by the sophistication of will power that runs through modern griot culture. The need to create and tell stories possesses so many black artists like a counterspell against bad infinity, and the need to make music did that for my father. Also I’m told that while I was in the womb he and my mother were up ‘til dawn every night writing together, so I think it’s literally in my DNA, and I feel fortunate for that.

Our history as we know it as black artists is so often censored, suppressed, and completely distorted, that we have to militantly mark our lives with their true insignia…

If our names are in some ways our destiny, your own name seems so fitting for the creative work you do. Is there a story behind how you got your name? Was it your father’s choice?

My name, yes, it’s grandiose, a bit mythic, sometimes people wonder if it’s given or invented, sometimes I wonder what’s the difference but it’s all up on my birth certificate, doubtless. I think it was a mutual decision, my parents had just fallen in love and eloped and conceived me and been on the kind of natural high that new beginnings foster, so I guess they wanted to go full concept on giving that energy a name and a meaning and a life. I’m told I used to spend the time while my dad was composing, hours on end every day, practicing writing my name on a notepad, the way kids pretend to be working alongside their parents, so I guess I was into identity and identification even before I knew the words. And as outlandish my name as it is, I love that it’s two dactyls.

What are you working on now? Can you give us a glimpse?

Right now, I’m super excited about the book I’m finishing up for Fence called Hollywood Forever, but as I finish assembling it, it may take on the title Love Stories, or it may need two titles like Go Find Your Father / A Famous Blues. It’s a kind of sensual tabloid that almost laments its own bravery like a 1960now edition of Downbeat, meets Jet, meets Life (the magazines). Here are a couple of pieces from it up on Everyday Genius. Also related to Go Find Your Father / A Famous Blues, I’m creating an archive of diaspora artists discussing fatherhood and at the book release in LA later this month, will debut a sound installation featuring this work. (Feel free to send submissions to that to AstroandAfrosonics@gmail.com and listen to clips at the Afrosonics Tumblr.) And the next-next is a sort of prequal to Go Find Your Father / A Famous Blues, a work about my father’s life before I was born centering around his relationships with Ray Charles, Sam Cooke, Bobby Womack, and his own parents. Another living myth that pivots on the real to access its magic.

Check out the book trailer below:

I seen it happen from EtatdeSiege on Vimeo.

If you want to meet Harmony, here are some upcoming readings

- Saturday, July 12 (LA book release!) at 7PM: Pop Hop in Highland Park

- Wednesday, August 6 (NYC) at 7PM: Poets House Showcase Reading Series with Yusef Komunyakaa & others

Additional link:

- Harmony Holiday’s Go Find Your Father/A Famous Blues