I found Fela last night.

I found him at the New York premiere of the arresting doc about his life, Finding Fela, directed by Oscar-winner Alex Gibney, and with a driving soundtrack by Fela Anikulapo Kuti himself.

The brilliance of Finding Fela is in the juxtaposition of director Bill T. Jones’ tale of his efforts to bring the Afrobeat pioneer’s larger-than-life story to the most improbable of places — Broadway, against a rendering of Fela’s life as told by the people who knew him, loved him and committed their lives to his vision. The film’s effect is twofold: it confirms both the audacity and the artifice of Fela! the musical, while it renders an intimate portrait of Fela, the man.

Seeing Fela! the musical both on and off Broadway, I was awed by the energy of the show, and the way it carried me back to The Africa Shrine, his famous Lagos night club, which I’d experienced as a young woman visiting Lagos in the ’80s. Fela! also helped a new audience understand the key aspects of his life — the musical influences that helped him pioneer the Afrobeat sound, the role his mother played in his life, the violent retribution he faced at the hands of Nigeria’s brutal dictators and how important the face-painted, hip-gyrating Queens were to his performances. Having the phenomenal Afrobeat band Antibalas on stage gave the show added verve. That was certainly a lot to pour into a stage musical.

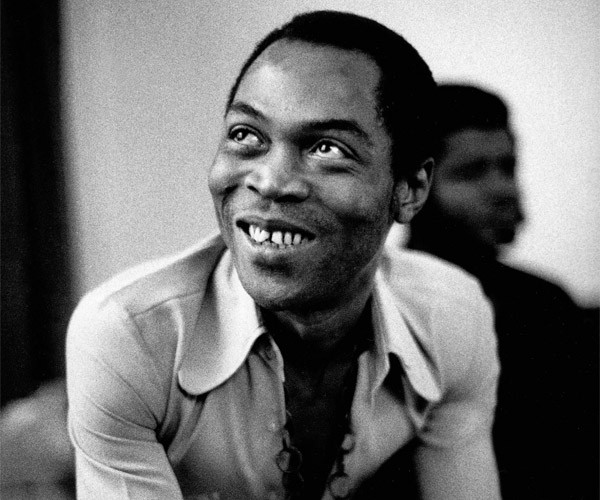

And yet. Finding Fela, richly shot by cinematographer Maryse Alberti, reminds us of the power of documentary film — a power that even a brilliant actor’s performance cannot replicate. A power that supersedes concerns about entertaining a live audience. When you see Fela talking to his fans or being interviewed or showing the scars from jailhouse beatings; when you see him dancing to his own music; smoking gigantic spliffs; turning back to give a band member the cold eye for messing up; when you see him in his mink coats with his wives encircling him; when you see him rant with heartbroken eyes about his mother’s death; when you see him claim that making love spiritually will keep you from getting AIDS; and you come to understand the disturbing denial that lead to his death (details that Jones purposely chose to omit from the Broadway musical), you know that this was a complex, passionate man. Yes, he changed the course of history, but he was a man nevertheless.

And when you hear his own son speak of the danger his father’s choices wrought upon his family; or hear from the extraordinary Sandra Izsadore (left, with Fela) how she was his lover, mentor and guide; or listen to his two biographers break down his upper-class beginnings or explain how the evolution of his music coincided with the changes in his life, you understand just how much you did not understand about this revolutionary man, who was also a son, a father, a friend, a brother. And nothing can compare to hearing his son, Femi, speak of his father’s funeral as you witness the slow-and-steady turn-out of a million people to see him laid to rest. To see Fela’s body lying in his clear casket. That is the power of the best talking heads coupled with the best archival footage — the best documentary film-making. It renders intimacy.

And when you hear his own son speak of the danger his father’s choices wrought upon his family; or hear from the extraordinary Sandra Izsadore (left, with Fela) how she was his lover, mentor and guide; or listen to his two biographers break down his upper-class beginnings or explain how the evolution of his music coincided with the changes in his life, you understand just how much you did not understand about this revolutionary man, who was also a son, a father, a friend, a brother. And nothing can compare to hearing his son, Femi, speak of his father’s funeral as you witness the slow-and-steady turn-out of a million people to see him laid to rest. To see Fela’s body lying in his clear casket. That is the power of the best talking heads coupled with the best archival footage — the best documentary film-making. It renders intimacy.

The film is a bit too long. You may wish for slightly less backstage footage of Bill T. Jones directing his cast for the musical, and a bit less stock imagery of Nigeria’s infamous go-slow traffic. You may wish that the scene of Fela! cast members speaking to the audience after their performance at the new Africa Shrine in Lagos was not relegated to the end credits. Still, the film is compelling. And timely.

Indeed, as the world watches Nigeria’s feckless president, Goodluck Jonathan, do all of nothing to find the more than 200 still missing girls kidnapped by Boko Haram, as the terrorist group gains a deeper stronghold in the country, it’s more important than ever to honor Fela’s activism and be moved to take action. The story of this Nigerian activist’s use of music as a weapon against his country’s corruption and exploitation comes to us right when we need to be told.

“What did you think of the film?” his son Femi Kuti was asked by Moikgantsi Kgama, whose ImageNation Cinema Foundation hosted last night’s premiere (Rikki Stein, Fela’s longtime manager, was also part of the Q&A).

“It is impossible to put Fela’s life in two hours,” said Femi. “But I was very impressed. I cannot explain how happy I am. I am very happy.”

You will be too. Rush to see the film in New York, and other cities, so you, too, can find Fela.

Additional link:

Book Editor Bridgett M. Davis’ new novel, INTO THE GO-SLOW features Fela in its story of a young African-American woman searching for the truth about her sister in 1980s Lagos, Nigeria.