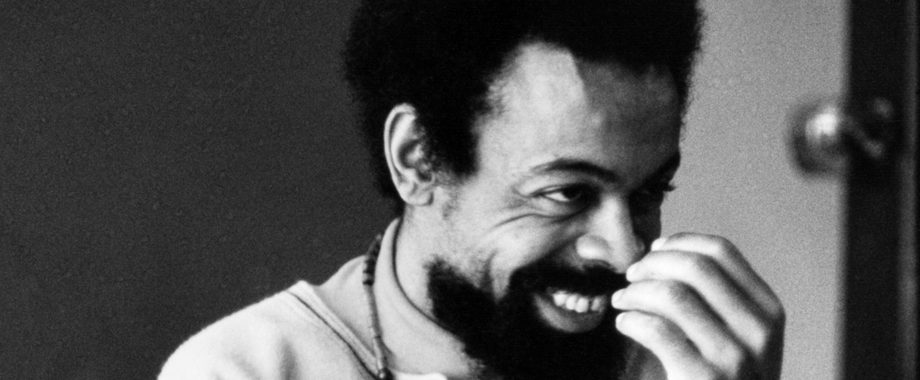

Roberto Carlos Garcia will be reading at this month’s Sundays @. . . on April 26. Here , in honor of National Poetry Month, he reflects on the legacy of the late poet and activist Amiri Baraka.

I miss Amiri Baraka. I miss his ferocity, his observations, and his powerful artistic expressiveness. I miss him tapping the side of the podium, keeping time to an imaginary metronome, improvising his own horn, or making sure the horn player (when there was one) was on time. I miss the faces of the young people in the crowd while Amiri Baraka was reading. How they marveled at the humor contained in his poetic truth, and the passion too. I miss his ability to take oppositional views, his antagonism. I miss his contrarianism. In his introduction to Somebody Blew Up America & Other Poems, Kwame Dawes keenly observes the following:

Baraka will tease us, toy with us, play with us, undermine us. He is the guy who stands on the playground teasing someone. We watch him and we find what he is saying funny because we always felt the same way about the guy he is teasing. So we think, “Hey, this guy is cool, let me join him.” Yet, the moment we open our mouths to start to throw insults, he turns on us. He changes the game. Or sometimes, he takes it further, as if he is trying to test us, now, and not the person he is teasing. He goes so far and we are left bedlamized in the middle—not sure where we stand. We stand there dumbfounded. We feel betrayed, and he is grinning. We walk away shaking our heads. This revolutionary figure does not offer us easy paths to the revolution.

There are no easy paths to revolution, and there are no all-knowing swamis either. Baraka didn’t pretend to be one. He was smart enough to know that followers, or a following, are not a sign of truth. His tenacity challenged you, us, to question his motives, and by extension the motives of everyone around us. You need to know what you don’t know, Jack. And what makes you think you know what you think you know?

Baraka’s anger was as important to his work as it was to his delivery. Anger is sorely missing from poetry today. As a young man of Caribbean descent with African roots, living in a racially polarized America, I needed the anger I found in Baraka’s poems. I still do need anger at racial injustice, economic disparity, and willful ignorance. They helped me come to terms with my identity and they allowed me to challenge the micro-aggressions around me head on. On the last day of the Dodge Poetry Festival there was a tribute to Amiri Baraka. Several well-known poets spoke about the impact of Baraka’s work on their lives. Poet Natalie Diaz expressed that although she didn’t know Baraka personally, his work gave her permission to be angry “it allowed us to be warriors again.” The epigraph to “Somebody Blew Up America” is a wise and articulated expression of the kind of anger I’m talking about “All thinking people oppose terrorism. But one should not be used to cover the other.”

Yet it seems that today’s oppositional narrative wants to be more—I’m not sure what exactly, maybe nuanced or sophisticated. Some of the blame for the lack of published angry poetry must go to the gatekeepers. Many writers and poets of color have stopped referring to editors as editors. The title of gatekeepers seems appropriate because they are keeping entry to the world of publication. That the “big” houses would not publish an icon of American poetry like Amiri Baraka should tell you all you need to know. Baraka took notice “When I was saying, ‘White people go to hell,’ I never had trouble finding a publisher. But when I was saying, ‘Black and white, unite and fight, destroy capitalism,’ then you suddenly get to be unreasonable.”

In his essay, “The Writing Class: On privilege, the AWP industrial complex, and why poetry doesn’t seem to matter,” Jaswinder Bolina writes:

…but poetry is supposed to be an art, which means it should at least attempt to represent the society in which it’s produced. It can’t fully do this if its primary mode of production inherently excludes large swaths of the population. The risk of such exclusions is that they limit the variety and appeal of the kind of writing produced in graduate programs. Nearly every complaint about contemporary poetry in the United States, whether in reference to the lack of diversity among those publishing it or to its opacity or to the very credibility of the genre itself, is rooted in this basic dynamic.

To take this a step further, poetry must also include its voices of discontent, if not feature them. However, the gatekeepers and the dominant mode of discourse, or what Erica Hunt calls “master narratives” determine agitation, instigation, antagonism, and contrarianism in literature today.

If Charles Bernstein had kept Erica Hunt’s essential essay “Notes for An Oppositional Poetics” out of The Politics of Poetic Form, if Graywolf Press had kept out Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric, if Agate Publishing had kept out Kiese Laymon’s How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America the landscape for oppositional voices would be more of a wasteland than it already is. In stark contrast, Baraka founded Totem Press and self published Preface to A Twenty Volume Suicide Note. Had self-publishing been the pariah it is today in the 1960’s, America might have missed out on what is arguably its most intense love/hate relationship with a poet. Preface to A Twenty Volume Suicide Note’s titular poem is an intense meditation on isolation and despair that remains relevant, and necessary to this day.

Lately, I’ve become accustomed to the way

The ground opens up and envelopes me

Each time I go out to walk the dog.

Or the broad edged silly music the wind

Makes when I run for a bus…Things have come to that.

And now, each night I count the stars.

And each night I get the same number.

And when they will not come to be counted,

I count the holes they leave.Nobody sings anymore.

And then last night I tiptoed up

To my daughter’s room and heard her

Talking to someone, and when I opened

The door, there was no one there…

Only she on her knees, peeking into

Her own clasped hands

Baraka’s brilliance lies in his ability to write “Preface” and also write a poem like “SOS.” To meditate on the singular elements of being while rallying Black people to overcome the struggle.

Calling black people

Calling all black people, man woman child

Wherever you are, calling you, urgent, come in

Black people, come in, wherever you are, urgent, calling

you, calling all black people

calling all black people, come in, black people, come

on in.

*

As we lose our elders we lose our connection to the old ways of opposing and protesting power structures. Once upon a time opposition or protest would see Baraka, James Baldwin, Gerald Stern, Maya Angelou, Jack Agueros and others march in defiance, but today’s poets have social media. Recently, in the wake of Michael Brown and Eric Garner’s murders at the hands of police, protest marches have sprung up all over the country. But it is via social media like Twitter and Facebook that America has heard the real story.

Poet Thomas Sayers Ellis, a poetic descendant of Baraka, is on Facebook teasing and challenging preconceived notions, trending narratives, and the fake corporate media propaganda machine. And there’s some anger in him too. It appears Ellis heard Baraka’s message loud and clear. Kwame Dawes writes that Baraka wanted “free thinkers,” and for the “self proclaimed revolutionary to be able to articulate the rationale of his or her beliefs.” Ellis has several challenges for his peers, chief among them is how to spot a poem that is feeding you an inherited cover story: he is a contrarian indeed.

How to Spot a Poem that is Feeding You an Inherited Cover Story #3

It requires that you have knowledge of another poem or two or twenty-two to complete the maturation exchange between the reader and the poem. The maze is meant to maze you, shock and awe.

How to Spot a Poem that is Feeding You an Inherited Cover Story #5

You never seen it off the page, in the world, getting in trouble, stumbling through a difficult autumn or coming out of a public toilet. It needs print and will wait months and years to achieve print. Speaks of itself in terms of feet or bio-speak, the weaponry of reputation. Its speaker ain’t nothing but an Eye Witness––saw something but wasn’t allowed to contaminate with it the truth of touch.

How to Spot a Poem that is Feeding You an Inherited Cover Story #9

The trigger is the title of the poem. The trigger is pulled the moment you start reading the poem. The trigger stays in the poem. The trigger ends the life of the poem. The reading life of the reader becomes addicted to triggers.

It is no surprise that such a mind would get a group of poets and musicians together to create a tribute album for Amiri Baraka. Heroes Are Gang Leaders (left) consists of Thomas Sayers Ellis, Randall Horton, Ailish Hopper, Mariahadessa Ekere Tallie, Heru Shabakara-ra, James Brandon Lewis, Ryan Frazier, Margaret Morris, Tyehimba Jess, Tracie Morris, Michael Bisio, Catalina Gonzalez, Prophet Lee Davison, Janice Lowe and Dominic Fragman. These poets, musicians, and vocalists have come together to spread some opposition, some contrarianism, and hopefully a little anger. Instead of going through the gatekeepers these engaged poets are making their own rules. Heroes Are Gang Leaders: The Amiri Baraka Sessions should be available soon. Also, this month Grove Press released SOS: Poems 1961-2013, a collection of over fifty years of Baraka’s poetry. There are some questionable interpretations of Baraka’s work, and inconsistent versions of various poems in SOS (as observed by Aldon Lynn Nielson on his blog Heatstrings). However, Baraka’s work is now available in the mainstream, and that has some benefits. Perhaps the winds are turning.

*

I think often of a reading I attended at St Marks in NYC. Baraka was reading and afterwards I went up to him with a couple of his books and asked for his signature. He said, “How you doing, brother?” You know how when you’re in front of someone you admire and you’re worried you might say the wrong thing? Well, that was I at that moment. I opened my mouth and all I could say was a cliché thank you. I said, “Thank you for being a voice I could trust, and even when I didn’t always agree with you, I trusted your honesty.”

There are some critics that still taint Baraka’s legacy at every opportunity. They ignore all that he learned and the transformations he underwent as a writer and poet. These critics would dismiss the great body of work he’s left behind. They’d denounce Baraka because of his early forays into anti-Semitism and homophobic language. Meanwhile TS Eliot and Ezra Pound are ever apologized for. Never mind that neither one attempted to establish their positions clearly on those issues the way Baraka did (see “Confessions of A Former Anti-Semite”, The Village Voice). Baraka should be lauded for coming through them a better man, with his integrity and his honesty intact. Amiri Baraka signed my book probably the same way he signed many others. But for me it’s a hopeful omen.

He wrote “To Roberto, in Unity and Struggle.”

Robert Carlos Garcia’s published works include the chapbook amores gitano (gypsy loves) Červená Barva Press 2013, his poems and prose have appeared or are forthcoming in Entropy, PLUCK!: The Journal of Affrilachian Arts & Culture, The Rumpus, 5 AM Magazine, Wilderness House, Connotation Press- An Online Artifact, Poets/Artists, Levure Litteraire, and others.

A native New Yorker, Roberto holds an MFA in Poetry and Poetry Translation from Drew University and is Instructor of English at Union County College. More info via his site here.