What’s been most interesting to me about Beyonce’s “Formation” video isn’t the video, but the way Black folk have been reacting to it. It’s as if, Beyonce is the Second Coming. Yes, I know that, for many she is. No one seemed to be immune from the global euphoria. Not celebs. For example,

Beyonce! Beyonce! Beyonce! #redlobster #hotsauce #blackbillgates #Formation EVERYTHING!

— Gabrielle Union (@itsgabrielleu) February 6, 2016

And certainly not Bey’s superfans, aka stans:

What is it that people–especially those who sing the song and video’s praises–are reacting to? Is it the case that it’s simply about Beyonce “doing something that was just for Black folk,” as has been suggested? That this is yet another example that we are, and have been, in a 21st Century “Say It Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud” moment vis a vis Black Lives Matter? Certainly, Beyonce wouldn’t be immune to feeling that, right? Are black people just hungry for representation in the mainstream cultural space?

As someone who views things through the lens of black progressive culture, I also wonder about Bey and Jay’s seemingly unfettered embrace of hypercapitalism: “Best revenge is your paper.” It’s possibly facile, but I’ll say it anyway: Isn’t there more to life than getting paid?

I’ll also be honest and acknowledge the following: On one hand, with great power comes responsibility. And when you think back to stars like Harry Belafonte, Lena Horne, Muhammad Ali or Nina Simone and the ways they consistently put their platforms to use for the cause of equal justice, the argument could be made that Beyonce comes up short. I also have to acknowledge that the Belafonte/Horne/Ali/Simone era was a different time. Beyonce is, is many ways a category of one. She’s a global superstar. Rather than being an “activist” marching on the frontlines, she pulls together things that are percolating the culture and serves them up. In many ways, it’s like being President of the United States: You act when there are enough public forces that push you to do so. Hence, Lyndon Johnson and the Civil Rights Bill. In this case, Beyonce took things we were familiar with: the Black Lives Matter Movement; Hurricane Katrina; New Orleans Bounce culture; colorism in the Black community, and put it up on a national and global platform for all to see. Through the video, she made a conversation-igniting piece of culture.

It’s true that I’m conflicted about Beyonce (and her husband Jay Z). Two things are also true: First, as Toure, the author of Who’s Afraid of Post-Blackness, said at our NBI Festival in 2011: “If there are 40 million black people, there are 40 million ways to be black.” Second, everybody’s not going to be as “woke” as we’d like them to be. No one person’s going to save us from anything. Not Obama, not Beyonce.

What I thought would be useful is to provide a roundup of some of the critical conversations that have taken place since last weekend when the “Formation” video dropped. Lot’s to think about here. Let’s get started:

YABA BLAY for COLORLINES

Yaba Blay, a scholar whose work focuses on skin color and identy, wrote this for Colorlines to give context to the use of the term “creole”:

For generations, Creoles—people descended from a cultural/racial mixture of African, French, Spanish and/or Native American people—have distinguished themselves racially from “regular Negroes.” In New Orleans, phenotype—namely “pretty color and good hair”—translates to (relative) power.

In this context, people who are light skinned, with non-kinky hair and the ability to claim a Creole heritage have had access to educational, occupational, social and political opportunities that darker skinned, kinkier-haired, non-Creole folks have been denied. In many ways, among those of us who are not Creole and whose skin is dark brown, the claiming of a Creole identity is read as rejection. And I’m not just talking about history books or critical race theory. I’m talking about on-the-ground, real-life experiences.

Jouelzy, who advocates for #SmartBrownGirls, created this 10-minute video in which she breaks down the cultural references in “Formation”. What I like about this is that she gives the perspective of someone who’s young and from the South.

THE FADER

Writers Naomi Zeichner, Doreen St. Felix, Anupa Mistry, and Judnick Mayard contributed to a four-way discussion on the video. Some of the points they made:

Doreen St. Felix: I want to talk further about cultural specificity. “Formation” is Beyoncé’s “The South Got Something to Say” Moment. This time, it’s femme, queer, and luxe. It’s wet. This time, Messy Mya is the prelude, Big Freedia the interlude, and no straight black men are to speak. Regional culture sometimes gets squashed in national narratives about blackness in the general public, since that term connotes a universality the global black experience obviously negates. . .”Formation” is an explication of her Louisiana and Alabama heritage so elemental it literally gets down to the level of food—”hot sauce in my bag,” etc.

Cultural specificity, I think, also explains what’s being misread as unfettered capitalism in the video itself. Black materialism, black luxe, is not radical. But the culture of self-luxuriating and self-adornment the visuals display—whether that be buying wigs for a regular-ass girl, or rocking Givenchy if you’re Beyoncé—is distinctly Southern and can be accessed across all classes. We like to look good, and we always will, no matter how much they take from us, no matter how hard they try to drown us.

Judnick Mayard weighs in:

Judnick Mayard: Beyoncé, too, has been traumatized by the events of the past decade in this country, specifically the past three years which have poured gasoline on a movement that seeks to literally protect black bodies by affirming blackness. Not conforming, not assimilating, but getting into formation and demanding information about who we are and what we seek.

That Beyoncé leads this charge is absolutely not surprising at all. She is the blackest pop icon since Michael Jackson. She married her black rapper husband who used to sell drugs in Brooklyn but now represents players running corporations and carries her beautiful black daughter—whose hair is not styled to assuage the media or the public, black or white—without a bother. She’s in the perfect space to speak to economic justice and to otherness. Beyoncé is always toted out as the Mother Teresa of blackness. She’s palatable for white moms across the country who want to feel “sassy” and “fierce” and dance with their daughter. She’s light and polite for those who want to sell you respectability as the only way to overcome, but Bey is nobody’s fool.

THE NEW YORK TIMES

The Times’ Jon Caramamica, Wesley Morris and Jenna Wortham likewise convened a roundtable to discuss “Formation”.

Music critic Caramanica writes:

In “Formation,” she returns to that city [New Orleans]; this time, she’s in scenes that suggest a fantastical post-Katrina hellscape, but radically rewritten. She straddles a New Orleans police cruiser, which eventually gets submerged (with her atop it). And at the end of the clip, a line of riot-gear-clad police officers surrender, hands raised, to a dancing black child in a hoodie, and the camera then pans over a graffito: Stop Shooting Us.

This is high-level, visually striking, Black Lives Matter-era allegory. The halftime show is usually a locus of entertainment, but Beyoncé has just rewritten it — overridden it, to be honest — as a moment of political ascent.

Critic-at-large Wesley Morris raises the question of her rootedness:

This woman’s blackness was never in doubt, but I wonder when you become this wealthy and this famous, and when that’s not how you were raised — friends, say, with the former Paltrow-Martins — whether you start to wonder or fear disconnection from what is, in Beyoncé’s case, your less affluent, Southern heritage. Her idea of swag in this song is keeping a bottle of hot sauce in her purse. That’s seriously, gloriously specific.

Staff writer Jenna Wortham weighed in here:

Some academics and Twitter activists criticized her use of the word “feminist” as a backdrop during her 2014 VMA performance and highlighted the contrast between a song like “Flawless,” a triumphant anthem that flaunted her independence, and “Partition,” where she sings about trying to be hot for her husband.

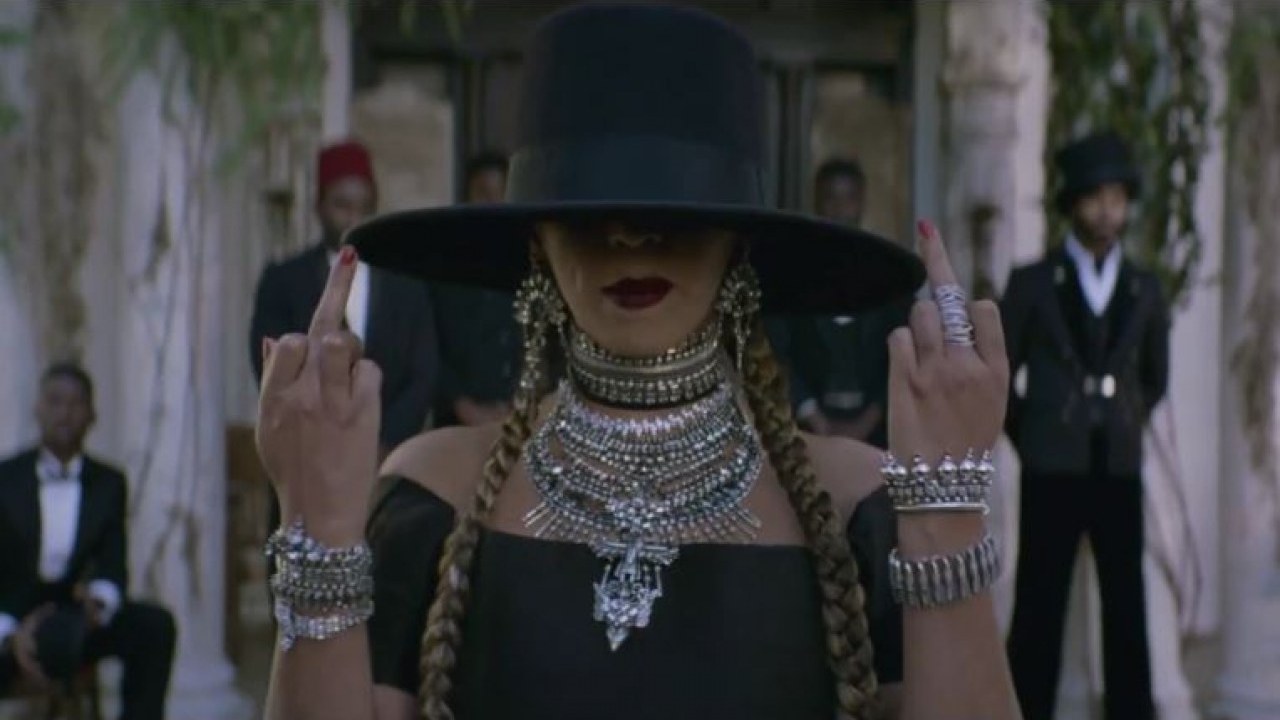

Personally, I think she can have it both ways: I think she can delight in her sexuality and express uncertainty about what it means as she moves through the seasons of her life, which is how I read that stunning shot of her holding up her middle fingers, her perfectly painted gothic mouth, wrists and neck dripping in pearls and jewels, her face barely visible behind a low-brimmed hat.

18. If I learned one thing this week, it is that we are starving to see ourselves in power. We yearn to celebrate the vision of it–even when we know it is a ploy, a hologram. Our hunger, no matter how potent, no matter how righteous, cannot transfigure pop stars into revolutionaries. It cannot supplement community power with what it manages to extract from corporate media.

21. Beyoncé is a logo. Beyoncé is a commodity. Beyoncé is a production. Beyoncé is a distraction. Beyoncé is a ruse. Beyoncé does not actually exist.

Bey, I hear you trying to unapologetically assert your Southern Blackness when you sing, “My daddy Alabama, momma Louisiana. You mix that Negro with that Creole make a Texas bamma.” I’m here for it. I can support that, even though you do not acknowledge the complicated, and often divisive, nature of colorism inherent in Creole identity politics. But, showing Hurricane Katrina inspired images and inserting yourself into the storm narrative is just as insensitive as using Katrina’s aftermath as a conversation starter when you meet a New Orleanian. Our trauma is not an accessory to put on when you decide to openly claim your Louisiana heritage.

As powerful and pro-Black as this song and accompanying video are, no matter how much catchy Carefree Black Girl Magic is flowing from it, “Formation” is not the protest song or BLM movement anthem some people want to claim it is. No one would identify the song as such just by listening to it.

In all honesty, you’ve let the Internet interpreters do all the hard work for you. It seems like déjà vu of “Flawless” and the discussion surrounding your status as a feminist. It’s one thing to borrow and build upon Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s powerful words. It’s another to take a story of suffering that is not yours and copy and paste it into your music video. You’ve constructed a market for self-affirming feminist music based on another feminist, but using New Orleans Katrina-scape as a backdrop for your pro-Black anthem is not encouraging—it’s inconsiderate. In the end, it feels forced, calculated and falls flat.

What do you think? Comment below!