While a lot has been published on the auteurism of filmmaker Charles Burnett, very deservedly so when positive and questionable when negative, his UCLA film school/L.A. Rebellion underground Black filmmaking group contemporary Billy Woodberry hasn’t received near as much acclaim. But that’s because those people have never seen 1983’s “Bless Their Little Hearts” – and up to last week I was ashamedly one of those majority.

Excuses aside, multiple screenings kept escaping my grasp, but the film that is classically, as critic Brandon Wilson remarks, “more admired than seen,” finally gets the restoration it deserves and now you’ll be able to see Milestone Films’ release of Bless Their Little Hearts at New York City’s IFC Center beginning today, Wednesday, May 17th, alongside Burnett’s similar, longer admired, but more placid film classic Killer of Sheep (1978), now on DCP. That Burnett also wrote and served as director of photography for Bless… makes these screenings even more special.

Bless Their Little Hearts was added to the National Film Registry in 2013 and newly restored by Ross Lipman for the UCLA Film and Television Archive, with digital restoration by reKINO (Warsaw).

At its base, Woodberry’s film (which began principal photography in 1979) centers on the crippling toll that joblessness takes on a married couple and their children. But at its core, it is about the everyday lives of all Black people, in particular Los Angelenos, struggling to maintain or establish a basic human dignity among a system destined to keep the women overburdened, the men infantilized, and them all grossly ineffective.

Dour as that sounds, it doesn’t come close to being ‘poverty porn’ due to the nuanced performances and the honest and civilized perspective that Woodberry and Charles Burnett bring to a then seldom-seen narrative. This narrative has thankfully since been brought to the screen via other Black filmmakers in other creative ways, but the everyday perspective that these creators seem to follow has seldom been duplicated.

One can write about Burnett all day (and read tomorrow’s interview with him), but Woodberry, still creating and changing the game over three decades later, is the focus here. StylisticallyBless… is transcendent. While deftly relying on its early 1980’s Los Angeles environment, growing more dangerous by the minute with Crip gang graffiti noticeably taking over one scene and an intermittent physical danger surrounding our male lead and his children, shades of Boyz in the Hood and Menace II Society potentially making young Ronald and Kimberly into future O-Dog’s and Brandi, it’s the powerful unfurling of the characters that makes this film operate in such a lifelike fashion.

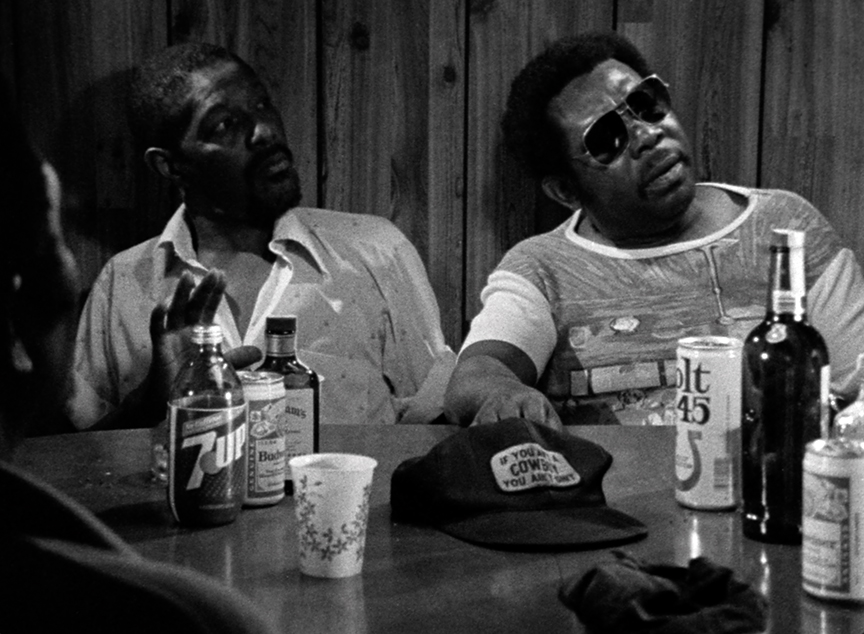

To put it plainly, Woodberry is a marvel with his actors. What he generates out of his leads Kaycee Moore (as Andais) and Nate Hardman (as Charlie) makes you marvel why these two barely made any other films. While that is evident throughout the film, from Charlie’s inefficiency of finding a regular job, to Andais’ struggle to maintain their meager household, it all comes to a head in the classic scene in which all the headaches, all the B.S. between the couple finally explodes in a nine-plus minute long argument centering on Charlie’s recklessness and Andais’ forlorn (life), all done in one take, the handheld camera rolling with their anger and bitterness toward each other. The scene is uncomfortable, but you can’t help but be transfixed – not like a car wreck, but like a geyser, with nature taking its necessary yet illuminating course.

While both actors are strong here, it is Moore who makes you emotional, when after a long day at work, knowing her man has done her wrong, is so strong, with a look that you’ve seen in a Black woman before if you really know a Black woman. I know I’ve seen my mother and my wife walk in like that before, tired and beat up by the world (but for different reasons), and Andais can’t help but exclaim, “You stand there look at me ugly like that’s gonna make the situation better…well honey that ain’t gonna make it no better…I am tired, I am tired, I am tired…I done got tired, and old and ugly helping you dream your dreams.”

Damn.

Improvised or fully-written, its purity that Moore unleashes here, and her Andais should be among screen performance legends. Hell, she is, right now and forever.

But it’s not just the leads, the Banks children, the supporting cast, they mostly all shine brilliantly on-screen as very real-feel people trying to make sense of a world that has chewed them up and barely has the decency to spit them out at a chance of survival.

In many waysBless… is also about legacy – for the characters and for Black cinema. There is the obvious to Black cinephiles – little Angela Burnett, niece of Charles Burnett, in yet another of his projects, with her early woman-ness taking over scenes and the screen as she did in Killer of Sheep and will do so in My Brother’s Wedding (also 1983), with her real and on-screen little brother and sister in tow. An early scene in which Charlie’s ne’er-do-well friends plan a robbery is also echoed in Wendell B. Harris’ classic 1990 film Chameleon Street. In both, grossly un- and under-employed loser types talk a good game, but in the latter, Doug Street’s pals execute their failed heist, leading to events setting up the remainder of that film.

While Hardman hasn’t been seen in much since Bless…, neither has Moore, though she did appear as the stern aunt Haagar Peazant in L.A. Rebellion filmmaker Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust (1991) also coming off a new restoration and recent film tour. Something great must be happening in the world that the work of the L.A. Rebellion filmmakers are making such an impact once again. Rebellion alum Zeinabu irene Davis’ documentary Spirits of Rebellion: Black Film at UCLA is also on the festival and screening circuit, and deftly chronicles the history of these filmmakers. It’s indeed a must-see for all cinephiles and culture enthusiasts.

Since Bless… the Dallas, Texas raised director moved on to teaching and a focus on documentary filmmaking. Woodberry’s long conceived film portrait of Black beat poet Bob Kaufman, And When I Die, I Won’t Stay Dead (2015) was the opening film of MoMA’s Doc Fortnight in 2016, premiered at the 2015 Vienna International Film Festival and has been featured at festivals nationally and internationally. The following year, Woodberry’s short documentary, Marseille Après La Guerre (2016), a portrait of dock workers in post-WWII Marseille, many of whom were of African descent, also received international film festival, art house, and critical acclaim. The film is extra special as it pays homage to Senegalese film directing legend Ousmane Sembéne, who immigrated to France in 1947 and labored on the docks, further informing his sensibilities about working class as well.

As Milestone Films writes, “Woodberry continues to address some of his major themes such as institutional wrongdoing (Kaufman ended up at Bellevue Hospital, where he was subjected to shock treatment); a close evocation of setting (North Beach scene in San Francisco) and the profound presentation of a complex, drifting character.”

He has also appeared in Charles Burnett’s When It Rains (1995) and provided narration for Thom Andersen’s Red Hollywood (1996) and James Benning’s Four Corners (1998).

And earlier this year, Woodberry became a Guggenheim Fellow for “individuals who have already demonstrated exceptional capacity for productive scholarship or exceptional creative ability in the arts.”

See the exclusive theatrical engagements of both Bless Their Little Hearts and Killer of Sheep at NYC’s IFC Center beginning Wednesday May 17th, plus director Billy Woodberry’s 1980 short The Pocketbook, also newly restored.

BLESS THEIR LITTLE HEARTS official trailer from Milestone Film & Video on Vimeo.

Related Links: