By Curtis John

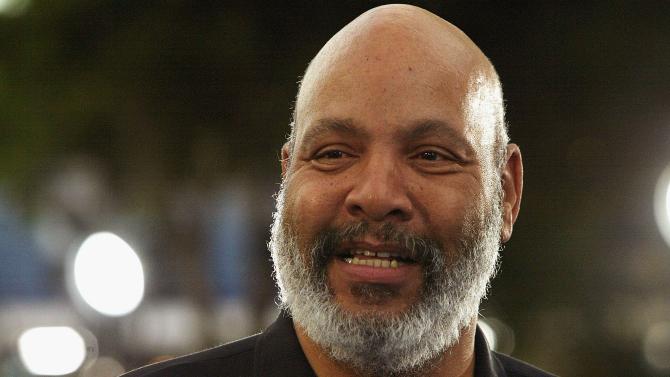

I was preparing to write on an entirely other topic for my first entry for 2014, but with the New Year’s Eve passing of actor James Avery, a man most television viewers knew best as ‘Uncle Phil’ from The Fresh Prince of Bel Air (NBC, 1990-1996), I was compelled to go in more emotionally charged direction.

I have been thinking a lot about manhood lately and what that means. There are no simple answers to something as complicated as to what being a man is in the 21st Century as our outlook on life and duties to our families and environment have changed drastically in the past twenty years. While men are still looked upon as having to provide financially for their families, though no longer solely in most cultures, they are also called upon to provide their families with emotional stability and a regular presence. And thankfully so. This is not brand new as it has been building as the norm for over thirty years now and has culminated in husbands and fathers who are rightly castigated for always staying out too late drinking with the fellas or not being a regular presence at Billy’s baseball game. However, building concurrently was the media perception of the inept or ‘wimpy’ dad and husband, especially in television sitcoms.

As far back as the early 1980’s and shows like Family Ties, continuing into the 90’s with Everybody Loves Raymond, and even further into contemporary TV with Last Man Standing and last year’s Guys With Kids, all among numerous other shows, too many television dads have been the butt of the joke, loveable but mostly clueless, and as the documentary series America in Primetime points out, “weak and bumbling [and] fairly politically correct.”

In the 1980’s it was Bill Cosby and his landmark classic television sitcom The Cosby Show that melted away the oblivious dad, and parents, taking back the house from smart-aleck kids who think they have the brilliance and life experience to get over on their folks. And The Cosby Show became an instant hit for this reason and more. “These people watching us happen to be making a statement,” Cosby states in a 1985 New York Times interview. “They’re saying to the networks, ‘Listen, this is the kind of thing we would like to see – not just a family and children running around the house but parents correcting and people hugging and kissing.”

Robin R. Means Coleman and Charlton D. McIlwain provide cultural history of this time period and before in their essay, “The Hidden Truths in Black Sitcoms,” which delves into how the comedic mediation of Black identity impacts and informs African Americans’ lives. Employing the use of different eras to help understand Black sitcoms, they highlight the “Non-Recognition Era” (1954 to 1967) that included shows such as Beulah and Amos n’ Andy as well as weak Black actor cameos in other show, and the 1972 to 1978 era of “Social Relevancy and Ridiculed Black Subjectivity” (a.k.a. the Lear Era), in which “the Black world that [Norman] Lear and others created during this period was a segregated one; the White world was largely invisible and appeared to have little interest or regard for the Black world,” as seen in programs like Good Times and Sanford and Son.

“The era of “Black Family and Diversity” (the Cosby years, 1984 to 1989) is one of the most promising five years that Black situation comedy has seen. The Cosby Show signaled a return to the Black subjectivity the Lear programming had promised but failed to deliver. The programming of the Black Family and Diversity Era was often focused on the family (as in Charlie and Co., Melba, and 227) and positioned African-Americans within their own cultural center, though not wholly segregated from the rest of the world. Series such as Cosby spin-off A Different World and the critically acclaimed Frank’s Place introduced Blackness as varied, sophisticated, and culturally relevant.” The diversity of politics, economics, and cultural practices, they continue, showed Blackness in a new light.

In the 1990’s, the first year of that decade specifically, and in a time after Means and Coleman’s ‘Black Family and Diversity’ era, it was The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air that eventually provided that example. Though the show began with the ‘fish-out-of water’ experiences of character and actor Will Smith and his comic adjustments to living with his aunt’s family in the exclusive California community of Bel-Air after getting into repeated trouble in his hometown of Philadelphia, and in the first season was often buffoonish in those aspects, it soon graduated into much more.

James Avery’s portrayal of Will’s uncle-by-marriage Phillip Banks, the high-class lawyer and eventual elected judge, established the show’s emotional and steady core once The Fresh Prince steadied in its comic beats. As Uncle Phil and Will realized that they both were not each other’s enemies, a revelation that became slowly unwound as they both battled each other for the family’s attention, Will realized something: that the discipline that Uncle Phil pushed for him to achieve was necessary. Avery’s Phillip Banks, partially because of the actor’s bulky 6’5” and rotund frame but also because of history as a young football player and post-injury political activist and the character’s rise from poor rural South boy to world-class lawyer, was no pushover and would not let this young upstart bowl over him. Uncle Phil’s own children were spoiled, yes, but also sharp and smart (well, not oldest daughter Hilary, as portrayed by Karyn Parsons). Uncle Phil demanded respect, and through his battles with Will to get it used both his own intelligence, but also humor and understanding to turn his nephew into a much more together young man – after a bumpy realization that Will would always maintain a clown-like yet loveable behavior. . Uncle Phil also realized that in trying to achieve perfection that he could be looser too – so they learned from each other.

Most of all Uncle Phil, and his wife Vivian (especially in Janet Hubert-Whitten’s portrayal of her), taught Will, and his own children – by example – the value of family. Taking Will in was a prime example of this, as was his discipline of the young man as if he was his own son. Will, seldom ever meeting his own father, never knew a man could embrace him like this and his pushback of Uncle Phil, while providing unending hours of comedy, was also psychologically 16+ years of combined hostility toward his own father. By adapting the family to accept Will, Uncle Phil showed a love of family, even when reluctant, that many feel has been lost in modern times. Some of the best moments in the show were when extended family would visit, and the comedy and drama that would stem from it.

The media war against Black manhood is ever prevalent as made obvious by the news coverage of the deaths of Trayvon Martin and Oscar Grant, the embrace of Tyler Perry movies that often scorn Black male characters (and yes, that includes the Madea character), among countless other examples. While television sitcoms and dramas are entertainment, they are also enriched by performers like James Avery who in his role of Uncle Phil provided a sterling example of how to be a man through love, discipline and humor – taking the Cosby model to a whole other level.

Thanks, Uncle Phil.

Related Links:

- James Avery obituary – CNN.com

- Will Smith – Every Young Man Needs an Uncle

- “The Hidden Truths in Black Sitcoms” in The Sitcom Reader: America Viewed and Skewed (2005)